Industrial Lodge Life

Two summers ago I spent one month working in the oil sands (nee tar sands) north of Fort McMurrary. While there I wrote most of the following post. I didn’t post it at the time, in part because I didn’t want to draw the attention of the oil company to the contractor I was working for. (We were warned they employ teams to scour the internet, looking for unauthorized photos. I don’t know about blog posts.) After I got back I was happy to move on to Vancouver life. But I’ve decided to finish it up and post it now.

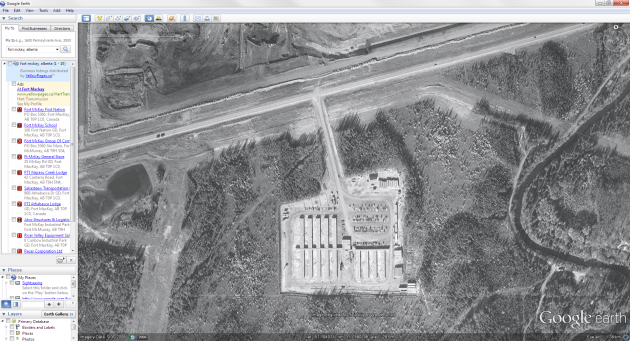

I live in an Industrial Lodge. From above, it used to look like this:

but it’s expanded since that photo was taken.

Most of the people living here seem to be pretty happy to be doing so, although I don’t talk to many folks outside my own crew. The lady at the Syncrude ID badge issuing office asked us where we were staying, and was enthusiastic when we told her the Oilsands Industrial Lodge. She said we were staying at the ritz, and she said so several times. The Syncrude ID office is a modular, low-ceilinged building, like most of the of operating office spaces in the mine areas. It’s not entirely easy to find in the chain-link maze of the Syncrude main site, but presumably most of the people who work here do eventually find their way to it, and I suppose the badge-issuing lady hears a lot of stories about accomodations. So it’s a fair bet that the Oil Sands Industrial Lodge is, indeed, a relatively decent place to stay.

I asked what the worst option was, and she was adamant that it was the Millenium camp that Suncor runs, but the worker at the next desk turned to tell us that they were revamping and renaming that camp. I’ve also heard plenty of stories about gang showers and rotten bunks in the original Syncrude dorms. Those descriptions sound something like mid-rise versions of logging camps.

I’ve also heard varying opinions on the range of quality of contemptary oil camps in the region. This may well be the ritz, I don’t know. I do know it’s strange. Not bad I guess, but strange.

For one thing, it is where it is. We’re a long way north here, and a long way out of town. I worked in this region some years ago, but back then our camp was more like a camp: a bunch of tents in the muskeg-forest wilderness, serviced by helicopter and ATV. This is something else, and although I knew what my destination was it was still strange to turn down the dirt road turning an hour north of Fort McMurry and find a complex.

It’s something like Moon Base Alpha meets Motel 6. The modular assembly means we’re sprawled out in a pattern of buildings not unlike the International Space Station, or some other notional space outpost. The main entrance is the only permissible one, all other exterior doors are emergency only. Through those main doors are a series of boot removal rooms, wherein outside footwear is to be removed on punishment of eviction. All the halls beyond are mopped to a spotless shine. So there’s also a sort of airlock, but for open-pit muck instead of oxygen.

The dining hall could easily be from a college residence, except for the demographic of the occupants. The TV room and games room might fit in there too. But the bulk of the lodge is in the halls of rooms and the connector hallway between them. A sort of ribs-and-spine arrangement with only two possible directions of movement: bedrooms to entrance, or entrance to bedrooms.

The access door to each hallway has an identical “ssshhh… night shift” sign, and looking down the hallways each is indistinguishable except for the laser-printed sign on the principal door, which is a number. You find your hall by the number.

The doors to individual rooms have plates on the outside which I first took for nameplates. I was ready to scribble my name but I noticed that no other door had a name, rather they are used to indicate if the occupant is on night shift, I suppose for the cleaning staff.

My particular crew is scattered over several halls behind those identical nameplateless doors, and I don’t know their numbers. Even if we lived close by there seems to be no such thing as impulse visiting; the doors are heavy and swing conclusively shut and lock automatically, no door stops are provided and nobody has bothered with improvised means for leaving their doors cracked. The distance between the far hallways and the dining room makes it a chore to stop in and see if anybody is hanging out. People do hang out in there sometimes. The dining hall is officially closed for cleaning after 8:30 but the staff are mercifully relaxed about that rule. On the other hand no one ever seems to hang out in the TV or games room, and I’m not sure why. There is a giant projection TV and a felt-top card table with a professional set of poker chips, but they all just sit there. In any case, the relevant line in the photocopied sheet of camp rules issued to each incoming tenant is:

TK no alchol or drugs (NO PARTIES!). TK

It’s an odd bit of punctuation, implying I suppose that we shouldn’t have to be told not to enjoy ourselves in a socially collective way, but they’re making the point strongly just in case. The prohibition on alcohol is an interesting one, and I’ll return to that.

The circular tables in the dining room are a good place to sit and chat, or would be except that for some reason the acoustics are terrible, some trick of echoes and HVAC noise is such that it’s difficult to hear what the person next to you is telling you, and a real effort to be heard in return. That’s a damn shame.

The one friendly space is the patio built out from the dining hall, when it’s not raining it’s a pleasant place to sit and smoke or drink bad coffee or eat a bowl of ice cream. All despite being situated between modular buildings and having a view only of wet gravel, a small microwave radio tower, a distant strip of black spruce matchstick forest, and the sky. The sky in Alberta is in fact quite entertaining, and they’ve provided comfortable lounge furniture, and conversation is easy. It is also outside, making it the only place at the lodge other than the parking lot where you can access the outdoors for a spell. My fellow erosion-control-crew members are wry, thoughtful, charming people and although I don’t know them well I enjoy chatting with them or sitting in silence. I’m struck over and over again that these intelligent capable men (and two women) are doing what is ultimately repetitive tedious work in a truly unpleasant location. But I suppose most work in the world is repetitive and tedious. And we signed up for this duty, and every last one of us is glad for the money. Many of my workmates have in fact worked on this contract before, although it is their first time being based from a work camp, rather than in the distant town.

“The Canadian Model for Providing a Safe Workplace (the Canadian Model) is a best-practice alcohol and drug policy that all stakeholders within the construction industry

across Canada can adopt and follow. The purpose of the Canadian Model is to ensure a safe workplace for all workers by reducing the risks associated with the use of alcohol and drugs. ”

The Canadian Model is more fully the “The Canadian Model for Providing a Safe Workplace”, A more accurate title would seem to be the Construction Owners Association of Alberta Model.

http://www.mhsa.ab.ca/2005canadianmodel.pdf

The other interesting institutional mandate is workplace injury norms. The reduction and elimination of job site accidents is an overwhelming goal. This is of course a good thing, and compare favourably with the yearly toll of forestry-related cripplings and deaths.

Although officially this is a dry camp, unofficially there are stories about people going into their rooms with suspicious packages, and someone saw an empty beer case on one of the cleaning staff’s trolleys. Maybe it’s difficult to keep this many men far from their homes and consistent relationships, doing physical labour, without much to do but the TVs in their rooms, and allow alcohol into the mix. That wouldn’t answer the question of whether a housing provider has the right to deny people access to alcohol. I’m confident they have the legal right to do so, and maybe they have the moral right as well.

We’ve all chosen to be here, to some meaningful degree. But coming up to work in the tarsands seems to mean accepting a bundled set of choices: you will do what you are told, you will not be officially injured, you will have your decisions about drugs and alcohol and partying made for you both on the worksite and off, you will consent to searches and tests whenever there is “reasonable grounds” for such (which apparently includes stumbling at work). I’m not sure how many people take a deep breath and work down the list of requirements, choosing to abide by each one before they come up here. I suspect most people decide they want to work in the oil patch and then at various points along the way learn what all they have consented to. This is hardly tyranny, but it doesn’t exactly feel like normal adult relations either. And since these relationships between us and the companies we are labouring for apply equally at the worksite and in the camp site, we are always looking over our shoulder. This seems like some alternative form of adulthood that I do not much care for.

That sounds melodramatic. Casual socializing, alcohol, your personal first aid kit. Again, none of these things is a crippling loss, and in the case of casual socializing I’m sure no one had any positive desire to prevent people working here from having a good team. Quite the opposite: the projection TV in the TV lounge is colossal, and their is a gambling table with a case of chips and what looks like real felt. But one way or another, this place is not conducive to companionship.

The song says:

Twenty-twenty-twenty four hours to go I wanna be sedated

Nothin’ to do and no where to go-o-oh I wanna be sedated

Just get me to the airport put me on a plane

Hurry hurry hurry before I go insane

There is an airplane, but it’s a lot further off than 24 hours. There is indeed nothing to do and nowhere to go. But since your living space is still effectively the workplace, sedation is not an option.